Like the Connectional African Methodist Episcopal Church Union Bethel was born out of sociological differences. In 1862 a small band of sixty (60) dissatisfied Christians led by a local preacher, Rev. William Foster, withdrew from St. James AME Church under a “sort of social and religious struggle between free mulattos and free blacks. The first place was located at Camp and Clio Streets and they called it “Bethel,” meaning “God is in this house.”

Between 1866 and 1883, eleven pastors served and the membership fluctuated as they worshipped in several places. In 1883, the congregation purchased the lot at Thalia and South Liberty Streets, the present location. They built a wooden structure which served as both a church and a school. In 1903 the church was officially incorporated under the name of Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church of New Orleans. In 1906 this building burned to the ground.

The foundation for the present church was laid in 1910 and the cornerstone is dated June 18, 1911. The upper level of the building was completed in 1921. In 1929 a building located at 1323 South Liberty Street was purchased and served as the first parsonage. During this period of growth, building and expansion Reverends Green B. Billops, W. A. Easton and J. B. Bell served as pastors.

It was in 1941 that Bishop Sherman Lawrence Greene appointed Reverend Howard Thomas Primm pastor of Union Bethel. He served as pastor from 1941-1952. This was a period of great growth and expansion. Union Bethel became known as the seven day a week church. During his pastorate at Union Bethel Reverend Primm established the Sarah Allen Child Development Center, This program set the pattern for Child Care across the City of New Orleans and later throughout the AME Church Connection. The Center was self-sustaining and received no funding from outside sources. In addition, he established the Edythe M. Primm Well Baby Clinic which employed a physician, two registered nurses, one student nurse and one clerk and the Primrose New-Life Building.

At the General Conference of 1952 Reverend Primm was elevated to the Episcopacy of the AME Church.

The Reverend George Napoleon Collins was assigned to Union Bethel following Bishop Primm. He worked with the congregation to organize and build St. Matthew A.M.E. Church in Ponchatoula, Louisiana. He organized the Foreign Aid Board which gave support to the overseas districts. Rev. Collins was elevated to position of Presiding Elder and then to the Episcopacy of the AME Church.

It was the Rev. T. W. Gaines, a son of the church, who led the congregation in the installation the beautiful stained windows. His faithful attention to the sick and shut-in was one of the greatest strengths of his pastorate.

During the administration of The Reverend Lutrelle Grice Long, renowned preacher, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. made his second proclamation against segregation and the use of public facilities when he was denied use of the Municipal Auditorium of New Orleans. Rev. Long opened the doors of Union Bethel to Dr. King. It was during this period during the height of civil rights movement numerous activities took place at Union Bethel. It was under his leadership the church was restored after having endured a horrific fire that gutted the building in 1962 and was restored in the fall of 1963.

The Reverend Nelson Pryor Patterson brought with him an emphasis on following the Discipline of the AME Church. He displayed a concern for others and inspired a new spirit of cooperation within the “family”. As a result Bro. Sidney Collier initiated the Celestial Drive which to the liquidation of the indebtedness of the church and parsonage.

During the administration of the Reverend Lorenzo G. Clarke the fellowship hall and the main sanctuary were renovated. He emphasized the development of the Youth Department, organized the Cathedral Choir and initiated the 8 am worship service.

November of 1982 Bishop Frank Curtis Cummings assigned the Reverend Thomas Benjamin Brown, Jr. as pastor of Union Bethel. This esteemed proclaimer of the Word served Union Bethel as pastor over thirty years. The Union Bethel Community Development Corporation was established by Rev. Brown in an effort to better serve the surrounding community in a larger capacity. Among the programs established: Homeless Prevention (Rental and Utilities Assistance), Feeding the Homeless, After School Tutoring, Youth Enhancement (YES), First Time Home Buyers Program, Adult Education (GED), Senior Citizens Program, Families in Transition from Welfare to Work and Mentoring Children of Prisoners.

On January 15, 2004 President George W. Bush visited Union Bethel and commended Union Bethel for its service to the community. Shortly following the presidential visit Union Bethel was awarded a grant to fund the Mentoring of Children of Prisoners Program. September 9, 2007 Union Bethel was named to the National Register of Historic Places. On April 24, 2014 Senator Mary Landrieu announced Union Bethel received a grant from U. S. Government FEMA of $3.4 million to rebuild the Four Freedoms Building.

“ ……It came to pass, that the Lord spake unto Joshua…… arise, go over this Jordan, thou, and all this people, unto the land which I do give to them,..”

October 2014 Bishop Julius Harrison McAllister assigned the Rev. Keith J. Sanders to the pastorate of Union Bethel. Rev. Sanders is a young, energetic, computer savvy educator who requested the church to “Give Change a Chance.” After only a short period of time after his appointment, Pastor Sanders was able to get the church’s mortgage refinanced and monthly payments cut in half. Financially astute, he revitalized the finance department and installed an accounting system that enabled the church to maintain accounting integrity. He has become the overseer of the rebuilding of the Four Freedoms Building. Rev. Sanders has assumed the role of Joshua with support of the congregation and moves forward to the “Glory of God

The church experienced many upgrades and much needed repairs during his three year tenure. Under his leadership, the church was able to purchase a new copier for the church office, make needed roof repairs from a leaking roof, repaint needed areas of the church, replace buckling flooring in the conference room, make bathroom upgrades including replacement of obsolete toilets, repair and replace damaged window sills and frames that were deteriorating from water leaks – costs that exceeded $30,000. In an effort to be proactive with building maintenance – the church now has regularly scheduled maintenance and inspections.

To enhance the music ministry, the church purchased a new sound system, a grand piano, and installed a platform for the Minister of Music and instrumentalists. To better accommodate members and shut-ins, we have an active website that features our services online with Bible Study and Prayer Requests. To better accommodate members, Pastor Sanders instituted a new App for Online Giving. Pastor Sanders placed special interest in the youth of the church by instituting youth focused Church and Sunday School. The Christian Education Department continues to experience growth spiritually and in numbers with its new programs (JAM) – Jesus And Me and (WOW) – Worship Our Way.

Bishops 8th Episcopal District

- Bishop Jabez P. Campbell – 1864-1869

- Bishop Thomas. M. D. Ward – 1869-1872

- Bishop Willie Nazerey – 1872-1880

- Bishop William F. Dickerson – 1880-1884

- Bishop Richard H. Cain – 1884-1888

- Bishop Benjamin F. Lee – 1892-1896

- Bishop James Crawford Embry -1896

- Bishop Josiah Haynes Armstrong – 1896-1897

- Bishop James Anderson Handy – 1897-1900

- Bishop Morris Marcellus Moore – 1900

- Bishop Charles Spencer Smith -1900-1904

- Bishop Moses Buckingham Salter – 1904-1908

- Bishop Edward Washington Lampton – 1908-1910

- Bishop Henry McNeal Turner – 1910-1912

- Bishop James Mayor Conner – 1912-1916

- Bishop William Henry Heard – 1916-1920

- Bishop Evans Tyree – 1920

- Bishop William Alfred Fountain – 1920-1924

- Bishop Abraham Lincoln Gaines – 1924-1928

- Bishop Reverdy C. Ransom – 1928-1932

- Bishop Sherman Lawrence Greene – 1932-1936

- Bishop William Decker Johnson – 1936-1948

- Bishop Monroe Hortensus Davis – 1948-1952

- Bishop Carey Gibbs – 1952-1953

- Bishop Howard Thomas Primm – 1953-1956

- Bishop Richard Wright – 1956-1958

- Bishop David Sims – 1958-1965

- Bishop Frederick D. Jordan – 1965-1967

- Bishop William P. Ball – 1967-1972

- Bishop Isaiah H. Bonner – 1972-1976

- Bishop Frank C. Cummings – 1976-1984

- Bishop George K. Ming – 1984-1992

- Bishop Robert Thomas, Jr. – 1992-1996

- Bishop Richard Allen Chapelle, Sr. – 1996-2000

- Bishop C. Garnett Henning, Sr. – 2000-2008

- Bishop Carolyn Tyler Guidry – 2008-2012

- Bishop Julius Harrison McAllister – 2012 present

Pastors

- Rev. William Foster – 1866-1867

- Rev. L. Lowman – 1867-1868

- Rev. J. J. Nelson – 1868-1869

- Rev. M. Lewis – 1869-1870

- Rev. Charles Hughes – 1870-1871

- Rev. W. P. Forrest – 1871-1872

- Rev. John Harper – 1872-1873

- Rev. George Bryant – 1873-1875

- Rev. Lorenzo Gardner – 1875-1879

- Rev. C. Atwood – 1879-1880

- Rev. James R. Grimes – 1880-1883

- Rev. J. D. Hayes – 1883-1888

- Rev. Albert Jones – 1888-1892

- Rev. Julius Willard – 1892-1896

- Rev. Thomas Williams – 1896-1897

- Rev. T. A Wilson – 1897-1902

- Rev. G. B. Hill – 1902-1906

- Rev. F. A Rylander 1906-1907

- Rev. Green B. Billops – 1907–1913

- Rev. W. A. Easton – 1913-1915

- Rev. J. B. Bell – 1916-1920

- Rev. E. D. Williams – 1920-1925

- Rev. W. A. McClendon – 1925-1929

- Rev. George Scott – 1929-1931

- Rev. J. B. Granderson – 1931-1932

- Rev. J. M. Brown – 1932-1941

- Rev. Howard Thomas Primm – 1941-1952

- Rev. George Napoleon Collins – 1952-1956

- Rev. Theodore W. Gaines – 1956-1959

- Rev. Lutrelle G. Long, Sr. – 1959-1972

- Rev. Nelson Pryor Patterson -1972-1974

- Rev. Lorenzo G. Clarke, Jr. – 1974-1982

- Rev. Rev. Thomas B. Brown, Jr. – 1982-2014

- Rev. Keith J. Sanders – 2014 to present

Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance

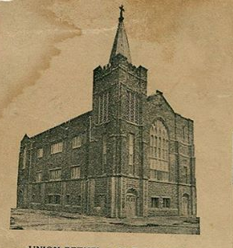

Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church occupies a large, three story masonry building at the corner of Thalia and Liberty streets on the northern edge of a New Orleans neighborhood called Central City. When completed in 1921, the church was surrounded by shotgun housing, much of which has been demolished for subsidized low-income housing. Immediately adjacent on one side is a 1960s housing project abandoned after Hurricane Katrina (August 29, 2005). On the other side is a just completed development of low-density traditional style subsidized housing. In front of the church, across Liberty, is a 1960s/70s high-rise elderly housing facility. The church was damaged by Hurricane Katrina and is now vacant awaiting restoration. Despite the damage (mainly at the rear) and a few earlier alterations, the church easily retains the bulk of its 1921 appearance. It is being nominated for local historical importance, and there is no question that someone from the historic period would recognize the building today.

The three story stucco over masonry building has an imposing façade some three-quarters as broad as the length of the side elevations. Its Gothic Revival styling is fairly intense. Emile Weil of New Orleans was the architect. The overall composition is that of a rusticated first story base (given over to offices and meeting rooms) with a two story auditorium above finished in smooth plaster. Historically access to the worship space was via staircases located in each corner of the building. (The present double door access at the center of the first floor dates from the 1960s.)

The façade is anchored by a weighty-looking and heavily worked corner tower that juts considerably above the main roof plain. The façade culminates at the center in a gabled parapet. The other corner of the façade is treated in a manner similar to the tower, but not as heavily worked (and not forming a tower). The tower is emphasized by a series of superimposed buttress-like elements with pointed tops at the second story, and to a lesser extent, wide pilasters with corbelled tops at the third story. Between the pilasters are louvered vents. The composition is crowned by crenellation and a faceted spire topped by a cross. At the center of the façade, below the gabled parapet, is a huge heavily molded pointed arch rising two stories. While the opening and its surround are original, the stained glass Gothic Revival window within dates from repair work subsequent to an August 1962 fire in the upper reaches of the church. Originally the space had a notable amount of wooden detailing and a series of narrow lancet windows.

The interior configuration is reflected on the principal side elevation. The seating is configured in a curving fashion along this long side (perpendicular to the façade) capped by a sweeping curved balcony. The balcony attachment on the exterior is seen in the expanse of wall between bands of windows. The bands feature pointed arch windows with wooden surrounds within squared off openings. The principal side elevation is also ornamented with buttress-like elements. It culminates at the rear in a strongly articulated gabled mass pierced by a large pointed arch opening at the third story level. The arch is emphasized with multiple layers of molding. Within the opening is a wooden treatment with three slender lancet arch windows. The ground level entrance at this corner is marked by a gabled treatment to echo that above. The strongly styled door treatment is identical to that found originally on the front corners. (One of the latter has been removed.) The Tudor arch form is re-enforced with a heavy molded cast concrete surround which ends at each side in an element resembling a ceiling boss. Pointed arch windows pierce the top of the double wooden doors. The space above, within the Tudor arch, is heavily molded and pierced by windows that are mainly of the pointed arch variety.

The secondary side elevation, where the altar is located, is mainly devoid of ornamentation. The rear elevation features a round window near the gable peak with a band of pointed arch windows below. (The latter were badly damaged in Hurricane Katrina, as explained below.)

Immediately to the rear of the church (about 2 or 3 feet away), and connected by a hyphen, is the Four Freedoms Building, constructed for enhanced church ministries in 1944. The two story stucco building is clearly of a later vintage but is compatible with the church. The upper story of the façade features square head windows with multiple panes of glass. A treatment similar to a hood mold caps the windows. The entrance to the building is within an arched opening, surmounted by a molding resembling a hood mold. Built with a flat roof, the Four Freedoms Building later acquired a gable roof configuration which provided a half story for storage. The half story was completely removed by Hurricane Katrina, leaving the building covered by the old flat roof. Nonetheless, there is notable interior damage due to Katrina (presumably flood waters). (The church is committed to a full restoration of both the Four Freedoms Building and the sanctuary.)

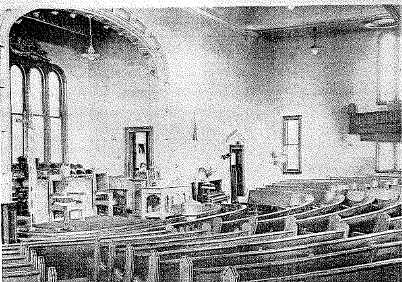

The sanctuary’s worship space can accommodate roughly 1500 people. As noted above, the pews are configured in a curving fashion. The balcony begins on the façade (in front of the great arched opening), sweeps down the long side elevation, and continues in front of the windows on the rear elevation. It is supported by thick pillars adorned on each side with a foiled arch. This foiled arch treatment is repeated (in the manner of an arcade) below the metal railing of the balcony. The altar railing is composed of delicate lancet arches formed of metal. Gothic Revival details extend even to the corner staircases. The newel posts are treated with various foil designs.

Alterations since construction:

1. Hurricane Katrina related: When the gable roof blew off the Four Freedoms Building, it fell into and knocked out a large window opening on the rear of the church. This is presently covered by plywood. Some of the windows at the second floor level were damaged and are covered with plywood. As noted previously, there is notable interior damage to the Four Freedoms Building.

2. Fire related: As noted previously, a fire in 1962 destroyed the roof of the sanctuary. The present interior ceiling treatment (wooden trusses stretching across a pitched roof) dates from after the fire. And, as noted above, the great arched opening on the façade was filled in with a new window treatment (although in the Gothic Revival style).

3. A historic photo survives to document the original appearance of the altar. Originally it was located within a large elliptical arch; now the opening is smaller and squared off. A set of arched windows has been removed. (A large cross is now in this location.)

4. Changes to egress: One Gothic Revival entrance has been removed from the façade. (An entrance was originally located at each corner of the façade.) Large double doors have been cut into the middle of the façade and stairs have been added to access the worship space from this area.

5. An elevator shaft has been added on the secondary side elevation, near the front.

Assessment of Integrity: The sanctuary easily retains sufficient integrity on the exterior and interior to be recognizable to someone from the historic period, and the attached Four Freedoms Building retains its exterior appearance. As noted earlier, the church is committed to a complete restoration of both buildings. (The delay has been caused largely by an insurance settlement.)

SIGNIFICANT DATE: 1921-1961

ARCHITECT/BUILDER: Emile Weil, architect

CRITERION: A State Significance of Property, and Justify Criteria, Criteria Considerations, and Areas and Periods of Significance Noted Above.

Union Bethel A.M.E. Church is locally significant in the area of social history as an important venue for African-American events in segregated New Orleans. And during the modern Civil Rights Movement, the church, because of its size, was an important venue for large mass meetings. Finally, the church is significant for the role it played in providing social services to African-Americans. The period of significance of 1921 through 1961 was chosen to encompass all of the foregoing significant roles.

Important venue for African-American events: When nominating the Booker T. Washington School auditorium (1942) to the National Register, the staff of the LA SHPO observed that the facility was the African-American municipal auditorium of its day. Union Bethel served in a similar capacity, largely prior to the construction of such “competitors” as the Booker T. Washington auditorium and the International Longshoremen Association (ILA) hall (c.1960). Long-time church members interviewed for this nomination noted that the school auditorium could handle even larger crowds than Union Bethel, and the ILA hall had the advantage of non-fixed seating. Hence it was more multi-purpose than Union Bethel.

Union Bethel was made available for all manner of non-religious events, from conferences to entertainment. An example of the former is the national conference of PORTIA, the Protective Order of Railroad Trainmen, which met in the church in late 1921. Entertainers who appeared there (as recalled by those interviewed for this nomination) include Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Roland Hayes, Clara Ward, and a group called Wings over Jordan.

Civil Rights Movement: The roughly 1,500 seating capacity of the Union Bethel auditorium was particularly important during the modern Civil Rights Movement. Additionally, the church was easily accessible from most points in the city and was reasonably close to the Central Business District, where various boycotts and marches were held. Church members interviewed for this nomination had first-hand knowledge of the various marches that started at the church. Participants generally came to the church to receive instruction and inspiration and to pick up their signs. The target of the march was typically Canal Street, the city’s principal shopping street.

A partial review of the city’s African-American newspaper, The Louisiana Weekly, during the civil rights years found three notable mass meetings held at Union Bethel. Paraphrasing one interviewee, if it was something really big [in size], it was at Union Bethel. The first known example occurred in March 1956. A reporter from The Louisiana Weekly, anticipating the event, wrote: “Orleanians are expected to tax the seating capacity at Union Bethel AME Church, 2321 Thalia, to attend a mass demonstration sponsored by the New Orleans Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance Sunday in observance of a ‘Day of Prayer’ and financial offering and reporting for the bus boycotting citizens of Montgomery, Alabama.

”Historian Adam Fairclough wrote of the event in Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana. The principal speaker was the acknowledged head of the movement in New Orleans, the Reverend A. L. Davis, pastor of New Zion Baptist Church. In March 1956, observed Fairclough, “Davis began preaching a more militant sermon. Presiding over a mass meeting of 2,500 people at Union Bethel AME Church, he declared his opposition to segregation in no uncertain terms. ‘I am issuing a call to 100,000 Negroes in this vicinity to rise up and let Perez [an arch segregationist in adjacent Plaquemines Parish] and his followers realize that the time is out for segregation and for all that this evil monster stands for.”

The Louisiana Weekly gave extensive front-page coverage to the meeting. The culmination of a day of activity that began in morning church services across the city, the afternoon mass meeting raised some $3,000 for the Montgomery bus boycott. According to the newspaper, it took over an hour to collect the money because the crowd was so large (“many lined in the street because of the lack of standing room . . .”). The $3,000 total, noted the reporter, was an incomplete one. “During the meeting Sunday, newsmen observed many persons unable to gain admittance into the jammed church sending contributions in relays from the sidewalk, . . . ”

A year later, in March 1957, a mass meeting at Union Bethel addressed the “bus situation” in New Orleans. (The Louisiana Weekly identified it as the second mass meeting on the subject, but there is no mention in the paper of the first.) “More than 2,000 freedom seeking Negroes,” reported the Weekly, were present at the meeting sponsored by the Inter-Denominational Ministerial Alliance. Organization president and founder, Rev. A. L. Davis, Jr., used the occasion to announce a “SEVEN POINT PROGRAM OF NON-VIOLENT ACTION.” Davis premiered a pamphlet outlining the seven points titled “A New Use for Old Wood,” referring to the iconic wooden screens used to divide the races on buses. The pamphlet depicted two screens nailed in the form of a cross.

In December 1961, Union Bethel hosted its most famous speaker, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. King had been scheduled to speak at the city’s Municipal Auditorium, as the keynote to an event sponsored by the Consumers League of Greater New Orleans. But the city rescinded permission the day of the event, once they learned that King was the speaker. The matter went through the courts during the day, with the courts siding with the city some two-and-a-half hours before the program was set to begin. According to church member Johnnie A. Clark, Union Bethel Pastor Lutrelle G. Long stepped forward and offered the use of his church. The evening began at the Municipal Auditorium, where “hundreds” gathered and marched through the business district to Union Bethel.

King, from the church’s pulpit, issued a call for a new “emancipation proclamation.” The president, he said, should issue an executive order “declaring all segregation unconstitutional on the basis of the 14th Amendment. . . . Abraham Lincoln merely freed the Negroes from the bondage of physical slavery. Segregation is slavery covered up with the nicety of complexities.”

Other civil rights churches and venues in New Orleans:

As was true in most other places, the Baptist church supplied much of the leadership for the civil rights movement in New Orleans. The acknowledged leader of the movement in the city was A. L. Davis, Jr, pastor of New Zion Baptist Church. His church survives to represent his leadership, and it was also an important location for various meetings (including a founding meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference) and training for non-violent protests.

In terms of the civil rights movement, all other churches and halls are in the “second tier” (after New Zion). Because non-violent protest activities were typically targeted to certain sections of the city, various churches were used for so-called “mass meetings.” (A church, or other venue, in the neighborhood of the proposed action would be chosen for convenience.) As noted previously, the hall of the International Longshoremen Association (ILA) was sometimes used. (This building, dating from circa 1960, survives.) The niche held by Union Bethel, and the ILA hall, was their use for really large meetings.

Exceptional Importance:

The National Register requires that properties be of “exceptional importance” if their significance occurred less than 50 years ago. Part of the significance for Union Bethel dates from 1956-61, the timeframe it was known to have been a venue for Civil Rights Movement events. Some of the modern Civil Rights Movement is now fifty years old and some is not – likewise for the civil rights history of Union Bethel. It would be arbitrary to define some of the civil rights movement (and Union Bethel’s association with it) as historic and some not. Where would you draw the line? It all helps tell the same story. (Per National Register Bulletin 22, “Guidelines for Evaluating and Nominating Properties That Have Achieved Significance Within the Last Fifty Years,” the 50 year threshold was not designed “to be mechanically applied on a year by year basis. Generally, our understanding of history does not advance a year at a time, but rather in periods of time which can logically be examined together.”)

Perhaps the best argument for “exceptional importance” rests on the historical force in which Union Bethel played a role: the modern Civil Rights movement. No one would dispute that this extraordinary movement is of “exceptional importance” in American history. African-Americans, aided by the courts and pivotal legislation, re-gained the fundamental rights secured some one hundred years ago during Reconstruction. Surely, the Civil Rights movement and the Cold War are the two most important historical phenomena of the second half of the twentieth century. As an important venue for large civil rights meetings, Union Bethel, at the local level, meets the “exceptional importance” litmus test.

Social Services:

Reverend Howard Thomas Primm assumed the pastorate of Union Bethel in 1941 with the dream of a “church that would serve the community.” A feature article appearing in the Pittsburgh Courier magazine section in July 1951, titled “Church 7 Days a Week,” demonstrates that the dream was realized. In the next year Primm would leave Union Bethel to become a bishop.

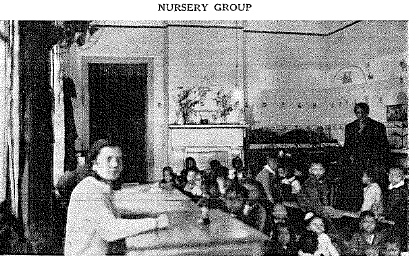

During his ministry the two story Four Freedoms Building and an educational building were erected to house expanded outreach of the church into the local African-American community. (The one story educational building, located to the right of the sanctuary, does not survive.) Erected in 1944, the Four Freedoms Building housed a weekly well baby clinic, a nursery (referred to as a “baby hotel” in one 1940s publication) and a kindergarten. All of these facilities were available to the public at large, not just church members. Named for its founder, the wife of the pastor, Edyth Primm, the well-baby clinic in 1951 had one doctor, two nurses, one clerk, and a student nurse from Dillard University. According to the Pittsburgh Courier article, it served some 2,500 babies per year. Also in the Four Freedoms Building was the Sarah Allen School, a kindergarten organized in 1942 by Mrs. Primm. Its enrollment in 1951 was 103. The school had the following paid employees in that year: director, registrar, 3 teachers, a dietician, a domestic worker, and a bus driver. “Childland,” the above referenced nursery in the Four Freedoms Building, provided daycare for some 400 children. The Courier identified it as one of three African-American nurseries operating in the city. (The other two were part of the Community Chest according to the article.)

Community outreach activities in the no-longer-extant Primrose New Life Center included boy and girl scout meetings, Teen Junction (a social venue for that age group), and a dining room where the public could purchase meals at a small cost.

Educational significance is not being claimed for the kindergarten because the LA SHPO does not have a sufficient context for evaluation at the present time. It seems clear, however, from the available sources that the cumulative effect of the daycare and the well-baby clinic (not to mention outreach programs from the no- longer-extant Primrose New Life Center) makes Union Bethel an important provider of social services within the city’s African-American community.

Historical Note:

Union Bethel was founded in 1862 when Reverend William Foster, of St. James AME Church, withdrew from said church along with sixty members. In 1903 the church was incorporated under the name Union Bethel AME Church. According to church history, the foundation of the present building was laid in 1910 and the basement (lower story) was erected in 1911. The LA SHPO suspects that this lower story was totally engulfed in the present 1921 construction.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fairclough, Adam. Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915-1972. University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Louisiana Weekly, various issues in late 1950s and early 1960s. Copies of pertinent articles in Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation National Register file.

Polk, Alma A. “Church 7 Days a Week.” Pittsburgh Courier Magazine Section. July 14, 1951.

Historic photos, copies in Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation National Register file.

Interviews with long-time church members: Verna Allen, Johnnie A. Clark, Jr., Leonard Gauthier, David Greenup, Lionel Stephens, and Althea W. Latimore.

Sanborn Insurance Company maps, 1940, 1951.